Content

Boost testosterone with personalized treatment plans

PSA and Testosterone: Are They Linked?

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a term you’ll probably become familiar with once you start getting screened regularly for prostate cancer (usually sometime after you turn 40, depending on your risk factors).

PSA is a protein produced by your prostate gland that doctors often use to assess your prostate cancer risk.

With testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) as an increasingly common treatment option for low testosterone, some medical researchers have raised the concern that increasing testosterone levels may also lead to an increased risk of prostate cancer, although current research doesn’t support a connection.

Stay with us as we dig deeper into the link between PSA and testosterone, including what elevated PSA can mean.

Content

What Is PSA?

As we mentioned, PSA is a protein made by the prostate gland. Doctors often use a PSA test to measure the amount of PSA in the blood. The results are often reported in nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL).

This test has become so mainstream that it has largely replaced the traditional method of screening for prostate cancer with a digital rectal exam, where a healthcare professional inserts a gloved finger into your rectum to feel if your prostate is enlarged. This test may still be performed alongside a PSA test, though.

There’s no single PSA value that’s considered abnormal, but your healthcare provider may be concerned if your levels exceed 4.0 ng/mL, especially if you’re at a high risk of prostate cancer due to factors such as a family history of prostate cancer. They may also be particularly concerned if this is a big jump from your baseline PSA levels.

Doctors also sometimes report PSA levels in ng/dL, which shifts the decimal place over by two. For example, 4.0 ng/mL would be 400 ng/dL. You may also see µg/L or mcg/L, which are the same as ng/mL.

Because PSA levels tend to increase with age, the threshold for further testing may be as low as 2.5 ng/mL for young men, while it could be 5 ng/mL for older men.

Some drugs, such as finasteride, which is used to treat hair loss and benign prostate hyperplasia, may increase your PSA levels but not your prostate cancer risk. For these men, doctors may also raise the threshold before they become concerned.

If your doctor is concerned about your PSA levels, they may send you for a prostate biopsy.

As we noted, elevated PSA levels can be a sign of prostate cancer (although in some cases they aren’t a cause for worry).

There has been a long-standing concern that higher serum testosterone levels may be related to the risk of prostate cancer. This idea was based on the fact that prostate cancer grows in response to androgens like testosterone and may increase PSA levels.

However, newer research suggests that the relationship between PSA levels and testosterone is complex. Abraham Morgentaler, MD, suggested the “saturation model” in the early aughts, which says that prostate cells only need a certain amount of testosterone to grow. Once a level of about 2.5 ng/mL is reached, adding more testosterone doesn’t cause further prostate cell growth.

Research is still ongoing to investigate this model.

Researchers are also continuing to examine whether there’s a link between PSA and testosterone in men with and without prostate cancer. Let’s look at each of these cases below.

There’s some evidence that PSA levels and testosterone levels may be linked in men with prostate cancer, although this is still under investigation.

In one study, researchers evaluated the risk of prostate cancer in a group of 646 men with an average age of 61 who had been diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Of the men in the group, 76 percent had PSA values over 4 ng/mL, and about 30 percent had testosterone levels that were considered low.

The researchers found that PSA and testosterone levels were correlated, with a lower PSA value significantly predicting lower testosterone levels. They concluded that for men with high-grade prostate cancer, a PSA under 4 ng/mL was a strong predictor of low testosterone.

However, it’s worth noting that a correlation doesn’t necessarily mean causality. Just because the two variables are often seen together doesn’t mean that one is causing the other. There could be another factor at play that influences both.

It’s been theorized that low PSA might also predict low testosterone levels in men without prostate cancer, but research hasn’t been conclusive.

In a 2021 study, researchers found that free (unbound to other proteins) and total PSA levels were good predictors of low testosterone in men in Nigeria seeking infertility evaluation.

PSA levels had good “sensitivity,” meaning they were accurate at identifying men with low testosterone, but had poor “specificity,” meaning they weren’t good at ruling out people who didn’t have low testosterone.

This was contrary to the results of another 2013 study, which evaluated 3,000 men with an average age of 52.5 and a PSA under 4 ng/ml. Here, researchers found that PSAs had a high specificity for low testosterone, meaning that high PSA levels were good at correctly predicting men who didn’t have low testosterone.

Other studies have found no relationship between PSAs under 4 ng/mL and testosterone, and more research is needed to completely understand how PSA and testosterone levels are linked.

Testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) has become a common treatment for men with low testosterone levels (hypogonadal men). It involves taking a synthetic form of testosterone (exogenous testosterone) to replace your body’s natural supply, whether through injections, gels, oral medications, or other forms.

TRT has the potential to raise testosterone levels back within the normal range, but there is the possibility of some side effects. Many of these side effects are mild, like rashes or skin irritation, but some researchers have raised the concern that it may increase the risk of prostate cancer.

What Does the Research Say?

Current research suggests that administered testosterone may increase PSA levels marginally but not necessarily the risk of prostate cancer, at least not to a significant degree. It’s important to keep in mind that this is a continuing field of research.

In a 2019 double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial using data from 12 American academic medical centers, researchers found administering testosterone to 790 men over the age of 65 led to an average PSA increase of 1.7 ng/mL. Still, only 1.9 percent of men had a PSA level over 4 ng/mL compared to 0.3 percent in the placebo group. The number of people who developed prostate cancer didn’t statistically differ between the groups.

A large 2023 study sought to evaluate whether testosterone replacement therapy administered to 5,204 middle-aged men with low testosterone increased the risk of high-grade (meaning aggressive) or overall prostate cancer risk.

The researchers concluded that there was no statistically significant difference in prostate cancer or high-grade prostate cancer risk between the two groups.

In a 2025 study published in the Journal of Urology, which is the official journal of the American Urological Association, researchers sought to evaluate the safety of testosterone replacement therapy for 5,199 men who received surgery for prostate cancer. The researchers found that the risk of cancer recurrence in men who did and didn’t receive testosterone was less than 2 percent and that there was no significant difference between the groups.

Other studies have come to similar conclusions. For example, a 2024 study found that administering testosterone therapy to men with prostate cancer who weren’t receiving active treatment didn’t lead to a higher rate of needing to switch to active treatment.

What Else Can High PSA Be a Sign Of?

Although high PSA may be a sign of prostate cancer, it can also be caused by other conditions, such as:

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) – non-cancerous prostate enlargement

Prostate infections (prostatitis)

Recent ejaculation or bike riding

Some medications, like finasteride

Older age

Anything else that might increase prostate inflammation

Doctors consider these factors when evaluating your PSA levels and referring you for further testing.

Although testosterone treatment may help many men undo the side effects of low testosterone (like erectile dysfunction, for example), no medication is without potential side effects.

TRT is not for everyone. It may increase the risk of:

Acne or oily skin

Sleep apnea

Increased red blood cell count (polycythemia)

Cardiovascular issues in some men

Clinicians weigh the benefits and risks of TRT carefully before administering it, especially in older men or those with heart problems. Your healthcare provider can help you understand the potential risks and benefits.

Conclusion: PSA and Testosterone

Total testosterone levels and serum PSA levels do seem to be linked, although exactly how they’re connected is still under investigation.

Men with lower PSA often seem to also have low T levels.

Current research doesn’t support that TRT increases the risk of prostate cancer, at least not to a significant degree.

PSA rises slightly with TRT but usually stays within safe limits.

Regular testing and follow-ups with a provider are essential for early detection of issues for men undergoing TRT.

If you’re thinking about undergoing TRT, it’s important to first consult your healthcare provider about the potential risks and benefits. You can discuss these with your primary healthcare provider or a specialist, such as a urologist or endocrinologist.

You can talk to a licensed professional and access at-home testosterone testing kits through Hims, all without the need to go to an in-person clinic.

It’s especially important to undergo regular prostate cancer screening once you hit a certain age. Most guidelines recommend screening regularly once you hit 50, or at 40 if you have predisposing risk factors.

12 Sources

- Amadi C, et al. (2021). Is serum PSA a predictor of male hypogonadism? Testing the hypothesis. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10065314/

- Bhasin S, et al. (2023). Prostate safety events during testosterone replacement therapy in men with hypogonadism. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2813293

- Bragg K, et al. (2024). Testosterone therapy as an isolated risk factor for venous thrombosis: A case report. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11290813/

- Cunningham GR, et al. (2019). Prostate-specific antigen levels during testosterone treatment of hypogonadal older men: Data from a controlled trial. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6823728/

- FLores JM, et al. (2025). Testosterone therapy in men after radical prostatectomy for low-intermediate organ-confined prostate cancer. https://www.auajournals.org/doi/10.1097/JU.0000000000004267

- Flores JM, et al. (2023). The relationship between PSA and total testosterone levels in men with prostate cancer. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9359436/

- Glina S, et al. (2021). Is serum PSA a predictor of male hypogonadism. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10065319/

- Kaplan-Marans E, et al. (2024). Oncologic outcomes of testosterone therapy for men on active surveillance for prostate cancer: A population-based analysis. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666168324002143

- Mejak SL, et al. (2013). Long distance bicycle riding causes prostate-specific antigen to increase in men aged 50 years and over. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3572135/

- National Cancer Institute. (2025). Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. https://www.cancer.gov/types/prostate/psa-fact-sheet

- Rastrelli G, et al. (2013). Serum PSA as a predictor of testosterone deficiency. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23859334/

- Wei JT, et al. (2023). Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/early-detection-of-prostate-cancer-guidelines

Editorial Standards

Hims & Hers has strict sourcing guidelines to ensure our content is accurate and current. We rely on peer-reviewed studies, academic research institutions, and medical associations. We strive to use primary sources and refrain from using tertiary references. See a mistake? Let us know at [email protected]!

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. The information contained herein is not a substitute for and should never be relied upon for professional medical advice. Always talk to your doctor about the risks and benefits of any treatment. Learn more about our editorial standards here.

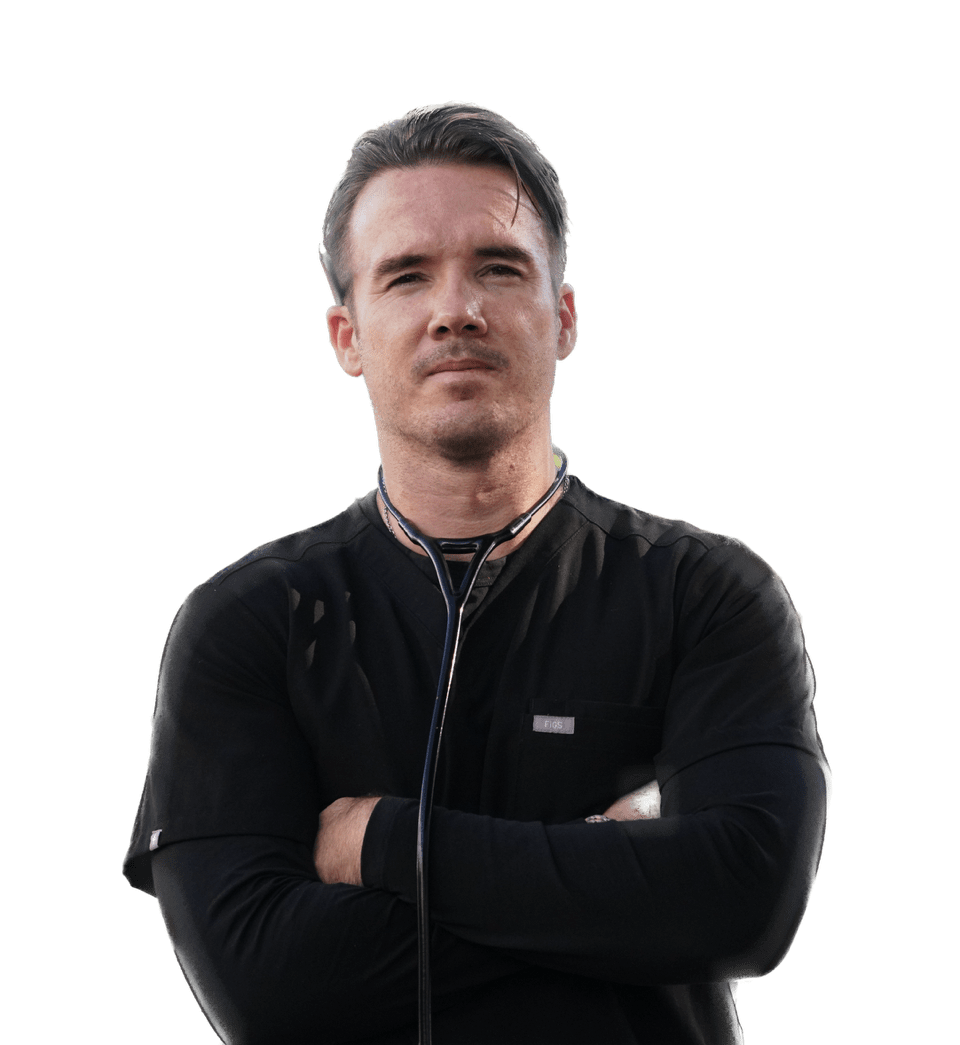

Darragh O’Carroll, MD

Basic Information

Full Name: Darragh O’Carroll MD

Professional Title(s): Board Certified Emergency Physician

Current Role at Hims & Hers: Medical Advisor

Credentials & Background

Education:

Bachelor of Science in Human Physiology - Boston University, 2007

Medical Doctorate - University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine, 2012

Training:

Internship & Residency - Los Angeles General + USC Emergency Medicine, 2016

Medical Licenses:

California, 2013

Hawaii, 2016

Board Certifications:

Experience & Expertise

Years of Experience: 14

Contributions to Hims & Hers

Medical Content Reviewed & Approved:

List pages or topics the expert has reviewed for accuracy

Media Mentions & Features:

Why I Practice Medicine

Health is never appreciated until it's gone. There’s nothing more satisfying than to save, change, or improve the health of someone in need.